Search the Republic of Rumi |

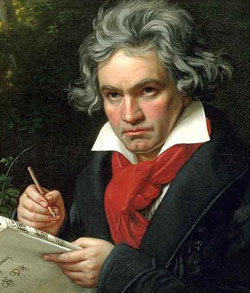

DAWN The Review, Januray 4-10, 2001 Beethoven: Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony lies on the top shelf in my study, in the form of two cassettes which I purchased from Rhythm House in Bombay nearly ten years ago. I have never had the heart to hear them. I fear that after I do, there would be nothing left for me to look forward to in music. Heard melodies are sweet, those unheard, sweeter, said the romantic poet John Keats. I love both, Keats and Beethoven, who were contemporaries and who focused their entire existence to prove the same unique point: it is not what you do but how you feel that really determines who you are. In fact, that was the common manifesto of that great Romantic Movement which was started by people like Beethoven, Goethe, Wordsworth and Coleridge and perfected by Byron, Shelley and Keats. As far as Beethoven is concerned, his life appears like a miracle, an impossibility, and if we read the story of his life with a ‘willing suspension of disbelief’ then it is certainly a fairy-tale written by the Creator Himself, who is otherwise known for writing non-fiction. Beethoven (1770-1827) came from a family of court musicians in Bonn (Germany), and moved on to Vienna when he was twenty-two. Already a musician of repute with some published pieces to his credit; he was still in search of perfection and was delighted to take lessons from the legendary composer Haydn. However, upon realizing that the old master was rather lenient in correcting Beethoven's mistakes, Beethoven shamelessly ditched his mentor and kept on looking elsewhere until he had perfected his grip on the carft of music. Beethoven was born with the ego of a monster, the first pre-requisite for any great artist, but he also had the wisdom to learn the most important lesson egoists often fail to observe: the importance of taking lessons. While in his twenties, Beethoven had not only composed and published several sonatas, a couple of symphonies and one huge opera, but had also gained respect for being a very disciplined artist. Goethe, who was at first a little averse to this arrogant and tactless ego maniac, had to also admit in the end, ’I have never seen an artist more concentrated, energetic and fervent. Beethoven was not very interesting company. He was rude and bad-tempered, often quarrelsome and always visibly selfish. His capacity for self-criticism, so very evident in his approach towards music, would regretably disappear before an absolute arrogance where his behavior rather than his art were concerned. The man who never spared himself a single mistake in his music, barely ever bothered to correct a folly in his behaviour towards others at any point in life. This attitude isolated him from his friends and relatives, whom he had given every reason to hate him. Even at the peak of his agony, when it finally struck him that he had been the cause of his own miseries, he refused to correct himself. ‘O you men who consider me as quarrelsome, peevish or a hater of human beings, how greatly you wrong me,’ he wrote in his Will about two months before his thirty-second birthday. ‘You do not know the reason why I seem to you to be so. From my childhood onward my heart and soul have been filled with tender feelings of goodwill, and I have always been willing to perform great and magnanimous deeds. But reflect, for the past six years I have been in an incurable condition made worse by unreasonable doctors.’ Then he goes on to describe his loss of hearing, and how he feels isolated when someone hears the sounds of a flute coming from afar and Beethoven, standing next to him, is unable to hear anything. His deafness had injected a lot of self-pity in him but that could hardly be accepted as an apology for treating others like dirt all his life. It would still less be an excuse for him to deprive the widow of his brother Karl of the custody of her only son a few years later, and then still further down the years to drive the young nephew himself towards suicide attempts. But Beethoven could not see the human needs of other human beings, simply because he had never seen himself as a human being. He had only understood his existence in terms of music, and even his vast reading in philosophy and literature had not helped him understand life, they had only helped him understand music better. Even before he composed his famous Fifth Symphony, Beethoven had turned almost totally deaf. It didn’t affect his work though, in fact, it ended in bringing out the genius in him and resulted in his creating an astounding composition. His irritation at not being able to listen to his musicians had turned into anger and he perhaps had felt the need to take his revenge on circumstance by producing a masterpiece that was better than the ones he had produced until then. The opening notes of the Fifth Symphony have become the most famous 5 seconds in the entire history of music. And they deserve to be: they are the symbol of human endurance throwing a defiant challenge to fate and death. It is the exact translation into music of the thought he had put in his Will a few years ago: 'Come when you will, death, I will meet you resolutely.’ Beethoven was performing an impossible task: he could no more correct his musicians, simply, because he couldn’t hear them. He soon became unable to conduct his own performances for the same reason. Most remarkably, it was now impossible for him to correct his own mistakes even in the matters of craft. But by then he had stopped making mistakes in music, only improvements. ‘At the age of 28 I was compelled to become a philosopher,’ he wrote. ‘It has not been easy, and more difficult for an artist than for anyone else.’ The most remarkable anecdote of Beethoven’s life is the composition of his greatest masterpiece, his Ninth Symphony when he was in his fifties. By that time Beethoven’s visitors had started to communicate with him through writing as he had become unable to hear a single sound, let alone that of the trumpet. It seems too much of a miracle to be true, but it was in this condition that Beethoven conceived, composed, prepared and presented the greatest symphony of his life, and possibly the greatest symphony ever produced. He added a choral piece at the end, which was a lyric he had always wanted to set to music since his early days at Bonn. At the end of the first performance of the Ninth, one of the solo singers from Beethoven’s choir shook him by the shoulder and pointed towards the audience because Beethoven hadn’t been able to hear the clapping that resonated the hall. They were applauding a symphony its creator had never heard. And a greater symphony nobody has ever heard since then. Beethoven was fifty-four when the Ninth Symphony was first performed. Three years later he died. Years ago he had written, ‘(My loss of hearing) has brought me close to despair, and I came very close to ending my own life but my heart held me back, as it seemed impossible to leave this world until I have produced everything I feel it has been granted to me to achieve.’ That was Beethoven’s challenge to death and fate: nothing would stop him from achieving what he had been granted to achieve. And he proved it. The Ninth Symphony is a music that came from no other source except the depth of Beethoven’s own soul. To bring out music from within, it was perhaps inevitable that he first stopped listening to the music outside. To perform his impossible task, Beethoven had to be what he was. ‘O God,’ Beethoven had written in his will twenty-five years ago. ‘You look down on my inner soul, and know that it is filled with love of humanity and the desire to do good. O my fellow men! When you read this some day, reflect that you have done me wrong. And let him who is unfortunate comfort himself with the thought that he has found someone equally unfortunate who, despite all the burdens placed on him by nature, did all which was in his power.’ | As far as Beethoven is concerned, his life appears like a miracle, an impossibility, and if we read the story of his life with a ‘willing suspension of disbelief’ then it is certainly a fairy-tale written by the Creator Himself, who is otherwise known for writing non-fiction.

|

|||