Search the Republic of Rumi |

|

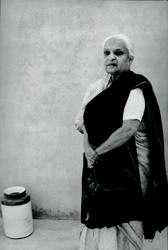

PROFILE Fatima Surayya Bajiya Bajiya belongs to an endangered species. Having imbibed the classical heritage of Indo-Muslim literature, Islamic history and puritanical etiquette on one hand and such profane interests as playwriting on the other, she is someone who is likely to find herself equally at home with the younger generation as well as the old. "I am more hopeful of the present generation than I am of my own," she says. "Apparently, the previous has got more to do with whatever is going wrong today. Maybe it’s because of the great migration that took place; people had to look for means of livelihood, a place to live, and so on. The people who were already settled here also had to suffer the consequences. In that struggle, nobody had the time to care about preserving the cultural framework." The grand migration of 1947 is a theme she can hardly avoid whether speaking on religion, drama, literature or morality (all very close to her heart.) Half the time she would be emphasising on the affinity between those who migrated and the ones who received them here. "We don’t have any problems, actually. Biases exist everywhere but we are the only ones who have earned a bad name. After all, what are the English and the Irish fighting over for the last forty years? Catholicism and Protestantism! What is happening between the blacks and the whites in America? True, they have made certain legislative provisions to secure some rights for everyone but see what a tough time they are now having even to sort that out. I think the Pakistanis are the best nation in the world…" This over-emphasis betrays an urgent sense within her – conscious or unconscious – that if she does not try hard things might be understood differently, maybe by her own self as well. At her most ideal she would say something like a reminder that the Holy Prophet (peace be upon him) never ordered a partition between the Muslim areas of Madinah and the Jewish quarters, and therefore all partition is, after all quite unnatural and superficial. At her most pragmatic she can be trusted to come out and say: "To say that we are only Pakistanis is hypocrisy. Why can’t someone say that I am Punjabi as well as Pakistani, or I am Baluchi as well as Pakistani." Bajiya’s stand on the nationality issue is again classical rather than political. She quotes the Fifteenth century Muslim sociologist and historian Ibn-e-Khuldun who defined asbiyat (roughly translated as ethnical identity) as a building block of communities as well as individuals. She goes on to distinguish between this asbiyat and tassub (roughly translated as racial or other prejudice), which is a threat to the integrity of communities. To achieve a balance between both is something she would ask you to achieve. Her popular drama serials, which mark her public identity more than her two low profile novelette and several humble stage plays, are just another way of bringing out her cultural philosophy. She finds no need to disown the Hindu heritage of what is today the Islamic society of India and Pakistan. In fact the famous (and sometimes long-winded marriage rituals) portrayed in her drama serials have often been criticised as imbibing Hindu ceremonies and promoting a pagan culture. On this issue Bajiya is unmistakable: "Islam is a religion, not a recipe for setting up a new culture. The term culture itself is a foolish term in a way, because people adapt to their geography, changing their clothes as well as modes of expression to suit their geographic conditions. This is irrespective of religion, which is something different. Islam was not revealed to create a new culture, because there already were so many great civilisations existing on the face of earth at that time – the Romans, the Persians as well as the great Indian civilisation, which provided perfumes, scents and a sense of beauty to the whole world. Islam came out, as the last religion, to provide the right beliefs but also to bring together all different cultures of the world – to accept them and benefit from them as you come across them." This kind of talk might give an impression that Bajiya is incapable of speaking in any terms except the huge scale of international relations. But that is not how she expresses herself when at her most creative. The best of her plays are about trivia from the lives of women, usually seen from behind the veil, which she weaves together to tell interesting stories filled with political and social insights. Only Bajiya could have written Abginay, Iltutmish, and Babur, plays about the greatest men in our history told from the perspectives of the women who shared (and controlled, as it appeared to some of the male viewers) their lives. "Men and women do not have separate worlds to live in. They share the same world. The confidence to live is as important for one as it is for the other." What seems a trivial issue of the women’s quarters can easily rock an empire just as what rocks an empire also has repercussions on the lives o f the women living in the secluded corners of that empire. The same message is brought out in her other plays, set-up in more contemporary situations. Agahi is a case against absentee landlord-ship narrated through the life of a woman, while simple pulp stories by A. R. Khatoon and Zubeida Khatoon (sometimes held down as our own equivalents of Mills & Boons) are transformed into vibrant interplay of grand human emotions when they come into the hands of Bajiya for adaptation. Shama could not have become such a big sensation of our television in the mid-70’s if it had attracted only the subscribers of women’s magazines. A strong, almost perverse, urge to blend the contrasts together is the ultimate drive behind whatever Bajiya has created – and it should be small wonder, then, that she expressed herself mostly through drama. It is also something that was rooted in the way she was brought up. As a child she received a conservative education dished out to her within the confines of her home ("only boys used to study for degrees,") strangely mixed with some home-based crash courses in driving and swimming. Growing up form there, Bajiya has come a long way to understand and respond to the changing realities of the time. But the flame that was passed on to her by a grandfather who was himself brought up in the heyday of Muslim revivalism still burns somewhere inside her. At the risk of sounding too fundamental, even simplistic, Bajiya boldly proclaims: "The renewed activity that may be observed in the Islamic centres of Europe and America today is not just a reaction within the Muslim community. Similar activities can also be seen among the Jews and the Christians. These are reactions to the break-up of the cultures. The positive forces of all these cultures have now come out to preserve themselves. Muslims revivalists like Iqbal had been preparing us for this for quite a long while now. Anyone who thinks Islam is his or her heritage alone is wrong. The fruits of Islam are for the whole world. Call me a fanatic if you like but that is what is happening and I can’t deny that." | The grand migration of 1947 is a theme she can hardly avoid whether speaking on religion, drama, literature or morality (all very close to her heart.)

|

|||