Search the Republic of Rumi |

|

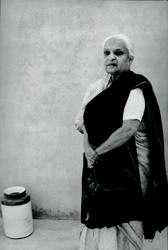

PROFILE: FATIMA SURAYYA BAJIYA World Lore As I take out the cassette from my small tape recorder, thanking Bajiya for her time and cooperation, she asks me to keep from disclosing some of the things and keep them off the record – names of some people she had mentioned during her conversation. She had said nothing particularly offensive about them, but I understand there is a strong desire to avoid controversies. Ironically enough, she is still capable of soliciting extremely contradictory impressions from the people she meets. Kamran, a college student recalls how he was treated by her a few years back when he escorted her to a school function: “We offered to pick up her bag, which was quite heavy. She declined our offer with extraordinary politeness, and insisted on carrying it herself. She called us beta, beta and showered affection and acceptance. I will never forget the sense of self-respect she instilled in me during those few minutes. Shireen (real name with held on request), a teenager who met her once in a milad gathering, had a different impression. “She was sitting there as if holding court and making general statements about ‘these young women of today who don’t know their duty’ while the women sitting around her were all listening with their heads bowed down. I have no desire to meet her again because I feel there was something hypocritical about that whole scene…” Perhaps there wasn’t. What Kamran and Shireen saw were two sides of the same coin: her Eastern upbringing. Although Bajiya practically lived the life of a woman of independent means, and almost an activist in her own sphere, she remains at heart an eastern Khala, even to this day – taking no more pride in her household chores than she does in her writings. “Dekho na beta, reading/writing is not the only responsibility I have. I live with my mother. There are things to be done. Footing the electricity bills, getting it corrected for overcharges, gas bills, guests; we are Masha Allah then siblings. Even if one or two of them visit everyday, then entertaining them, their children, is time consuming. So this is a very full life. Whatever time I get for my writings I consider more than what I deserve.” Going back to her eastern upbringing. “The confidence to live by my own set of values was instilled in me by my elders who would have been branded orthodox, had they been alive today. There have always been broad-minded families among the Muslims… I mean, where did I learn how to drive a car? I have not learnt it recently. Even though I did not have to drive our family car, my grandfather and my father wanted me to know how to do so. They wanted me to learn how to swim. We were not allowed to swim, of course. It was just to make sure that I would at least know how to get out of water and not drown in case of an accident. I never went to school but I was educated at home: Urdu, Arabic, Persian, English. I never felt any frustration. Men and women do not live in two separate worlds. The world they live in is one. The confidence to live in this world is important for women just as it is important for men. The lesson my maternal grandfather taught me was that ‘you are a human being, responsible for your own actions in the world and before God. Our responsibility ends with giving you the tools you need: education and training. Now we are withdrawing, just tell us whether we have given you the right training.’ We said (Bajiya frequently uses the royal pronoun) ‘yes, you have done that.’ I had no one to criticize me except God, whom alone I fear. That is how a child gains confidence.” Bajiya’s first novel grew out of the tales she used to listen to as a young girl from her domestic servants. Of cruelties committed by husbands, of criminal neglect on the part of delinquent parents, very much a part of the lives led by the working class. Hence she emerged as a ‘leftist’. She says with amusement, “Bernard Shaw or Bertrand Russell or somebody has said that every youngster is a leftist. But if he remains so for a long while, then there is something wrong with him.” Bajiya’s nana took care of the second thing. He Islamized the manuscript as well as the author and got the former previewed by Abdul Majid Daryabadi, Jigar Muradabadi and other stalwarts of literature. Bajiya’s heroines are usually remembered as conformists. They never rebel, they never take drastic steps, they never challenge the patriarchy. Bajiya says it is not so. “I have adapted two novels by A.R. Khatoon for television, Shama and Afshan. Now, these novels were written by a housewife thirty or forty years ago. The authoress had no experience of the world beyond her own home. It was an atmosphere where the girls were voiceless. But in my adaptations I made these girls speak out. My heroines are not dumb but she cannot run away from her parent’s home. This I cannot bear to show. I never thought of doing such a thing, how can my heroine? I want her to survive, but within her own environment. If you run away from your own surroundings and survive then what’s the big deal? Strangers don’t know you anyway. Huzoor ki dua hai beta, tum zara ghor karo, (she instinctively draws her duppatta over her silver-grey head as she mentions the Holy Prophet (peace be upon him), he says: “O Allah! Give me wusat in my home and make me dear to my own people.” In a nutshell, this is the simple philosophy of Bajiya’s feminism, if one may call it that. If you probe further into the issue of religion, she will perhaps bring in one of her favorite lines “Sachi baat bataoon, beta?” or “Mein batati hoon” and then explain to you that good people everywhere are the same – be it Pakistan, India, the Christian world or anywhere. “They are also like us. They speak different languages, profess different beliefs, live in different cultures, but they think just like us nevertheless. The reason being that the basic needs of life are the same for all people. So, the philosophy which Islam upholds is the philosophy which brings benefits to all people. When Muhammad bin Qasim was planning an invasion, some of his generals asked the religious scholars about the people inhabiting India, and were duly informed that they were idolatrous. Yet the Vedas, the Gita are books that talk about the Supreme Being. The Prophet (peace be upon him) stood up in respect at the funeral procession of a Jew, because the Jew was also a follower of a revealed book. The Quran has stories about other revelations. Who are we to deny the truth of those books?” Bajiya, if you had been in another land, and if you were not writing in Pakistan, what difference would it have brought to your writing? “Had I been born in Saudi Arabia I would have been writing about the Arab world. Had I been in England I would have been writing about culture. But now that I am a Pakistani, I am writing with a color that is typically Pakistani, and now I cannot, I do not want to change it no matter where I go.” What is this ‘Pakistani color?’ “It has a shade of the intellectual ethos of the subcontinent. It does not make any difference that Fatima Surraya Bajiya was born in Hyderabad, Deccan. Had she been born in Lahore or Khairpur, it would still have been the same. Because I know that there are many homes like my own.” And why did she choose A. R. Khatoon for adaptation? Actually, she did not. It was given to her by the people at the TV center. Bajiya finds it more convenient to write on her own. Adaptation is a somewhat tedious job. But she is all praise for A.R. Khatoon. “If a simple housewife writes a four hundred page novel, she deserves credit. She was living in a society which did not allow her a first hand experience of the outside world. When I was adapting Shama, a well-known female short story writer said to me, why have you taken on such a trashy thing? Before I could answer, another senior male critic and humorist said, “If it was not for A.R. Khatoon, how else did you evolve?” Which authors does Bajiya count as her main inspiration? “I respect everyone, and I read them all. From Egypt and Europe to … So much so that it sometimes borders on unintentional plagiarism! Consciously, something might have impressed me so much that when I sit down to write, it comes up. Let me tell you one incident. There was a story by Prem Chand, called Tuliya. I wrote a four episode serial on it – unconsciously.” This serial, by the way, was not written for television. Bajiya often writes for her own pleasure, and she can count up to 26 manuscripts which are bundled away some place in her house. Most of these will probably never see the light of day. “Whenever I write for television, it is because they ask me to, I never seek them out, TV wallo mein neh yeh karnama anjam diya hai, isay produce karo!” I want to discuss her historical play Iltutmish, but as I begin with “Coming to history…” she is carried away by her intellectual passion for history, and interrupts me. She is on her feet in no time, abandoning the corner where she was cozily ensconced on the carpet and takes me to a towering wardrobe. Inside there are history books… original sources, translations from Arabic and Persian, books written by biased orientalists, books written by devout fanatics, books written by … “Even if I decide to begin a project at midnight, I can do so, I have collected many books on history in my house.” As far as Iltutmish is concerned, she says, “You can’t really enjoy history unless you read controversial accounts of it. Unless you do that, you don’t get a real hold.” In the play, Bajiya succeeded in capturing the ethos of a bygone era and presenting the political forces at work in South Asia within a short span of fifty minutes. Earlier, she had written a series of historical plays about the women of the Abbasid dynasty. Abgeenay (1977) featured such historical figures as Queen Kheezran and Haroon Al Rasheed. It did annoy some conservative scholars who retorted, “When we were studying the history of Islam we did not notice that only women used to be the rulers.” Bajiya wonders whether the plays are still preserved in the PTV archives or not. She fears that it is unlikely, since the recording system has since been converted into a different format. A considerably recent production was Babur, broadcast a few years back. Once again, it was a typical Bajiya historical: the career of the first Mughal as seen from the perspective of the women related to him. Unfortunately, the PTV producers juxtaposed the title of each episode with the destruction of the Baburi mosque. This was indeed done in bad taste and many serious viewers were put off. Although Bajiya does not mention it, but I am quite convinced that she was herself among those who were disappointed. “This was not my idea. Not at all. I had deliberately avoided the theme of communalism. Babur had Raja Sangram executed by trampling him under an elephant’s foot. I did not depict that in the play. You see, there is already so much Hindu-Muslim hatred, we don’t suffer in Pakistan if we say things like that, but sometimes the Muslims living in India have to pay the price. Keeping that in mind, you have to overlook certain things.” If you ask her which one of her plays she likes best, she appears a bit uneasy about making such a selection, “I liked Agahi. The subject was very strong and pertained to the absentee landlordism. Dallas was poplar, so they launched Waris. There was pressure on me to wind it up quickly, but I persisted. I said if you want to end it, just stop it. I won’t change the story according to your demands.” Does she think there is any conflict between Urdu and the regional languages? “No, Not at all. The regional languages are jewels which will enrich Urdu, and get enriched in return. On the other hand, if you create a conflict between the languages, the whole nation will just turn mute.” | Bajiya’s heroines are usually remembered as conformists. They never rebel, they never take drastic steps, they never challenge the patriarchy.

|

|||

DAWN Tuesday Review, Aug 6-12, 1996

DAWN Tuesday Review, Aug 6-12, 1996